Vytautas the Great and Teutonic Order ravage Vilnius

Before becoming Grand Duke of Lithuania, Vytautas committed at least one disgraceful act that would bar any modern politician from achieving high office. In 1390 he led Teutonic knights in an attack on Vilnius and decimated the defenders of the Crooked Castle. However, he did become the grand duke and his reign lasted for nearly four decades. Moreover, his excellent rule brought him highest honors and history remembers him as Vytautas the Great.

Reise nach Vilnius

The raid on Vilnius at the end of summer 1390 was exceptional because alongside the Teutonic knights marched Lithuanian duke Vytautas and the future King Henry IV of England, who then was still known as the Earl of Derby Henry Bolingbroke (1367–1413). The assailants took and burned down the Crooked Castle where they killed Kazimierz-Karigaila, the brother of King Władysław II Jagiełło. The Teutonic Order launched the raid despite the fact that Lithuania, at least de jure, was a Christian land.

“

The raid on Vilnius at the end of summer 1390 was exceptional because alongside the Teutonic knights marched Lithuanian duke Vytautas and the future King Henry IV of England, who then was still known as the Earl of Derby Henry Bolingbroke (1367–1413).

For Vytautas, the year 1390 began with fleeing to Prussia for the second time, because of his quarrels with his cousins Jagiełło and Skirgaila. Angry and vengeful, Vytautas was instrumental in acts of war against Lithuania. The preparation for the raid on Vilnius began in summer.

According to the German chronicler Johann von Posilge, Henry Bolingbroke had 300 men with him, many of whom were experienced archers. Grandmaster of the Teutonic Order Engelhard Rabe, Livonian Master Wennemar von Hasenkamp, and Vytautas surrounded by Samogitian troops marched alongside them.

The march started in August and huge forces reached Vilnius by the end of the month, then proceeded to build two bridges across Neris. The siege of the city’s three castles began on 4 September 1390.

Wooden castle besieged

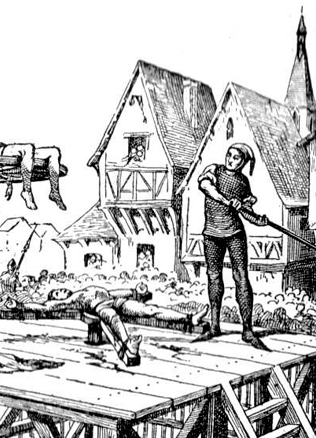

Johann von Posilge claims that the Crooked Castle was the primary target because it was the only one built of wood. Defended by Duke Karigaila and his men, the castle held on until it unexpectedly caught fire. Some maintain that it was sabotaged by Lithuanian traitors, as the attacking forces could not breach it.

The fire spread panic. English chronicler Thomas Walsingham claims that Henry Bolingbroke and his knights were the first to breach the castle and raise Henry’s flag on one of its walls. Henry’s books of financial records suggest Walsingham might be telling the truth, because it features a line of money paid to an Englishman, who had hoisted the Earl’s standard during the siege.

“

People rushed out of the burning castle. Karigaila, the brother of King Jagiełło, was among them. Many were captured and taken prisoners, others killed on the spot, many choked on the deadly smoke.

People rushed out of the burning castle. Karigaila, the brother of King Jagiełło, was among them. Many were captured and taken prisoners, others killed on the spot, many choked on the deadly smoke.

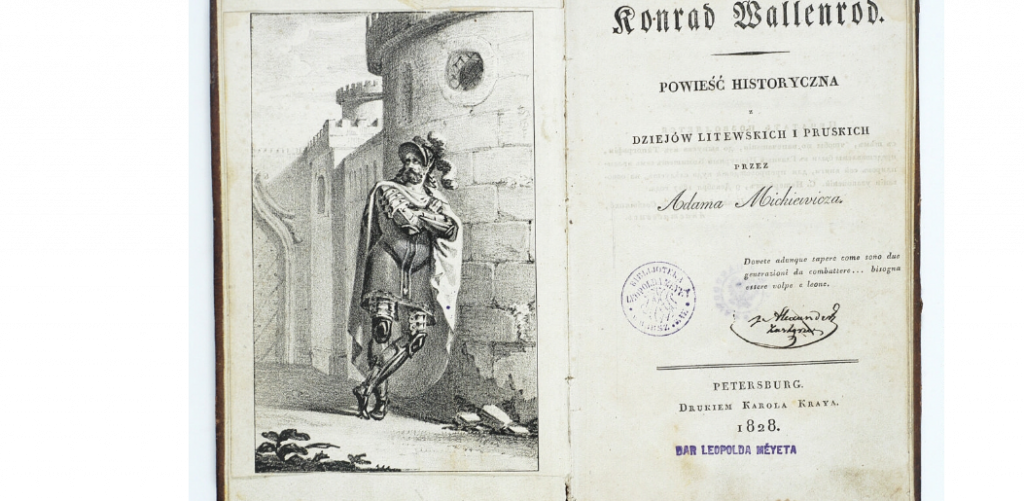

Grand Komtur of the Teutonic Order Konrad von Wallenrode wrote a letter to Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, shortly after the siege of Vilnius. In von Wallenrode’s words, the decisive charge took place on the sixth day of the siege and was successful at first attempt. About one thousand people perished inside the castle, dying by sword or fire. There, von Wallenrode noted, a number of “virtuous knights”, several Ruthenian princes, and Karigaila, the brother of a Polish king, met their death. Another two thousand people, old and young, were captured inside and around the castle.

The united army then made several unsuccessful attempts to take the two remaining castles before marching back to Prussia. They left on 7 October, having spent almost five weeks in Vilnius.

Various versions of duke’s death

Duke Karigaila’s death almost immediately emerged as a key development of the siege. Contemporary sources offer several hints. Wigand of Marburg’s chronicle says that after the castle fell “the king named Karigaila was among the many murdered”. The Chronicle of Archdeacon of Gniezno mentions that after the Crooked Castle caught fire, Karigaila died alongside its many defenders.

In Jagiełło’s eyes, the German knights were culpable for the death of his brother, but the order’s Grand Komtur Konrad von Wallenrode, wrote in a letter to German princes on 8 December 1390 that the breach caused a great commotion in the castle and that Duke Karigaila was killed because no one had recognised him. Von Wallenrode said his death was unfortunate, because if he was captured alive, he could have been exchanged for the German knights in Lithuanian custody.

His other letter, written in January 1391 and addressed to Queen of Poland Jadwiga says that no one was aware of Karigaila’s death until some Lithuanians from another castle broke the news.

More than two decades later, in 1416, Jagiełło’s envoys presented numerous complaints against the Teutonic Order in the Council of Constance. One of them reconstructs the 1390 siege of Vilnius and describes in vivid detail the murdering of Karigaila. The document says that the duke’s severed head was hoisted on a pike and his dead body defiled. The representatives of the Teutonic Order maintained that Karigaila had died unidentified.

“

Later still, in the 1520s, the Bychowiec Chronicle attributed the capture of the castle and the killing of Karigaila to Vytautas. Historian Maciej Stryjkowski’s “Chronicle”, first published in 1582, offers a similar narrative and places the blame on Vytautas who reportedly ordered to behead his cousin and hoist it on a pike.

Later still, in the 1520s, the Bychowiec Chronicle attributed the capture of the castle and the killing of Karigaila to Vytautas. Historian Maciej Stryjkowski’s “Chronicle”, first published in 1582, offers a similar narrative and places the blame on Vytautas who reportedly ordered to behead his cousin and hoist it on a pike. Another historian, Albert Wijuk Kojalowicz retold Karigaila’s death in his Historiae Lituanae (1650): “Here, in the eyes of his cousin, he lost his life. Vytautas ordered that his head be chopped off, put on a pike, and paraded around the camp: another loathsome testament to extraordinary cruelty arising from animosity among brothers.”

By Antanas Petrilionis